what it is ain’t exactly clear

(Buffalo Springfield)

The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born: now is the time of monsters.

- Antonio Gramsci

Where can we find the right

MONEY?

- What are our choices?

- What is money, anyway?

- Why does matter so much?

Money matters.

It’s how we pay for things.

FIDUCIARY Money matters.

It’s how we pay for income security in a dignified future, for some, and all,

as humans living together, and apart,

in society, through economy,

using money on a planetary scale

in the 21st Century, and beyond…

Fiduciary Money

- Mid-Century Modern adaptation

- of the 19th Century social innovation of the donative trust for generating income through investment to endow philanthropic grant-making foundations as forever machines

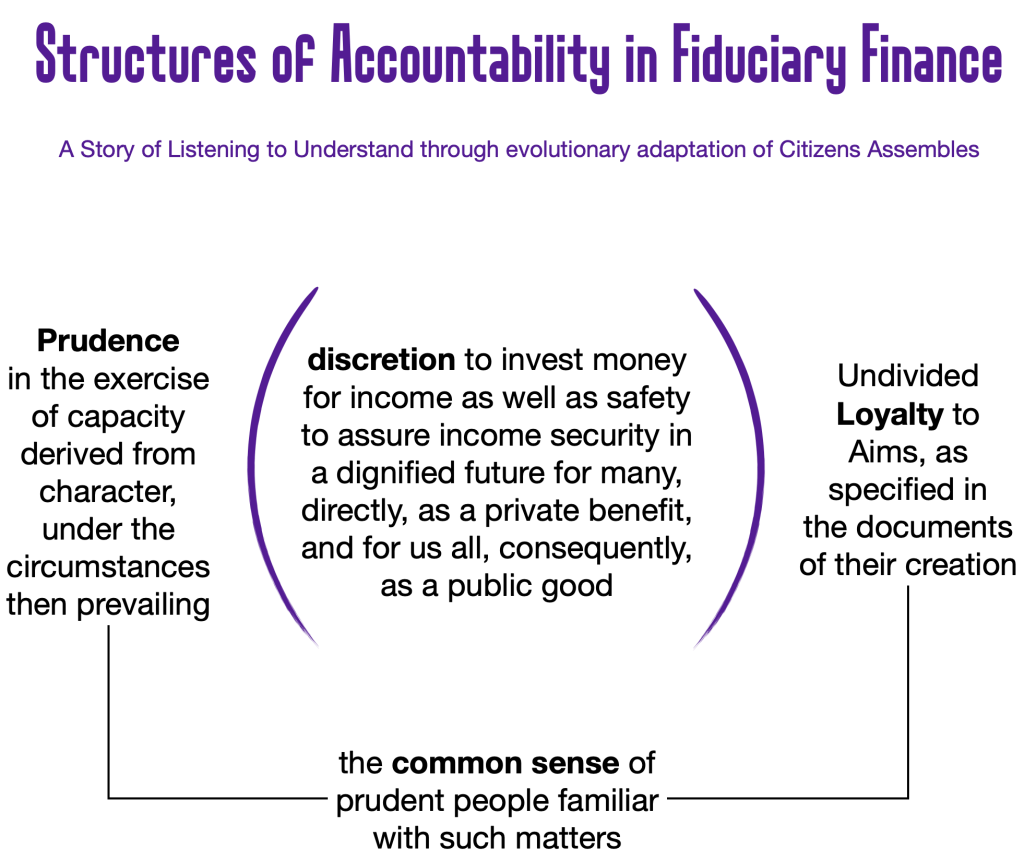

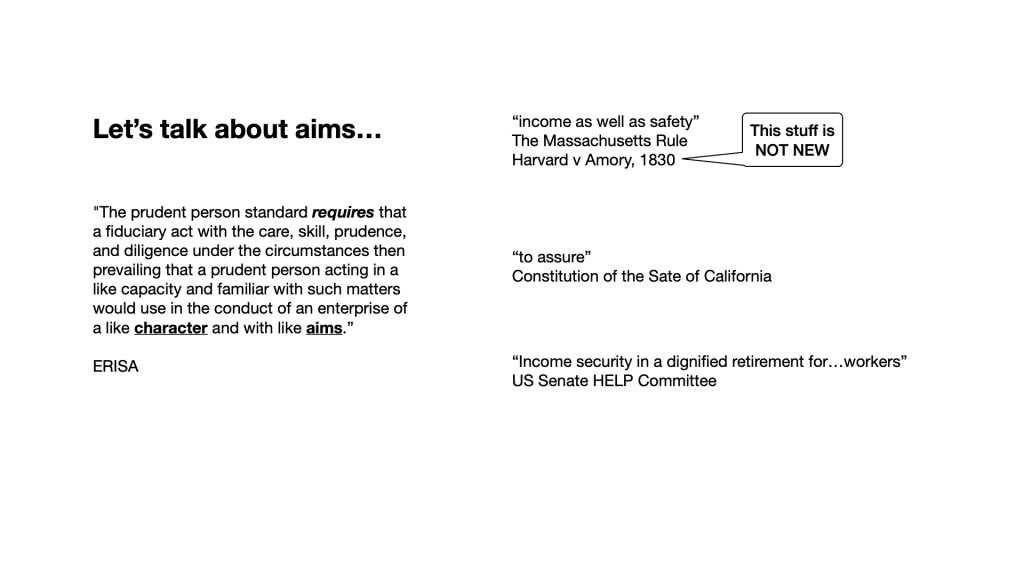

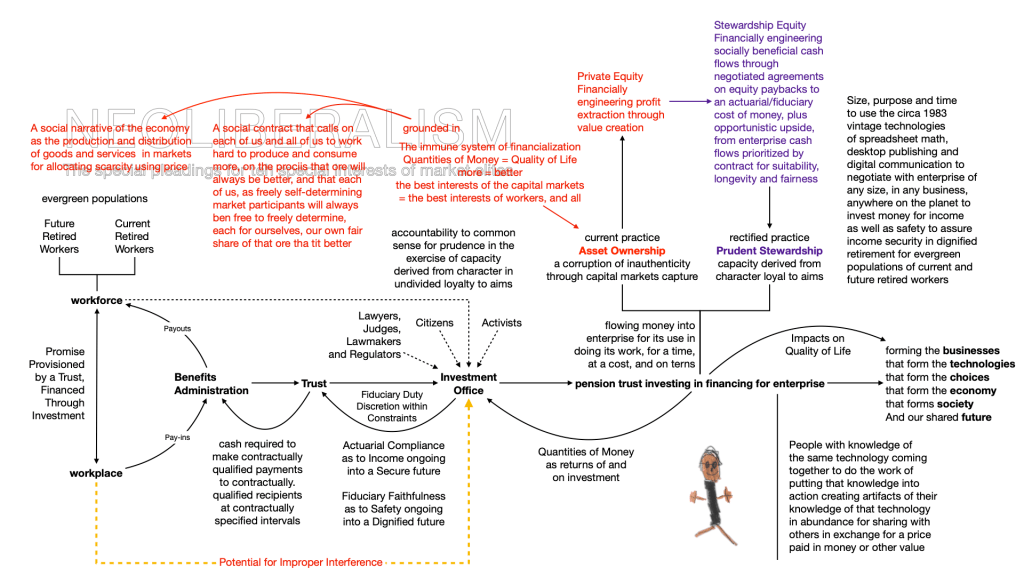

- to innovate social trusts for investing money for income as well as safety, within the legal constraints of fiduciary prudence and loyalty, to assure income security in a dignified future for so many, directly, as an earned private benefit, that it is also, of necessity, for us all, consequently, as a de facto public good

- for socially provisioning the social safety nets of Workforce Pensions as mutual aid societies for averaging the actual costs of making contractually calculated payments to contractually qualified recipients at contractually specified intervals across statistically significant populations of statistically similar individuals, by applying the statistical laws of actuarial data science

- accountable to the common sense of prudent people familiar with such matters, under the circumstances then prevailing

Fiduciary Money

- care, skill, prudence and diligence

- of the prudent person familiar with such matters

- under the circumstances then prevailing

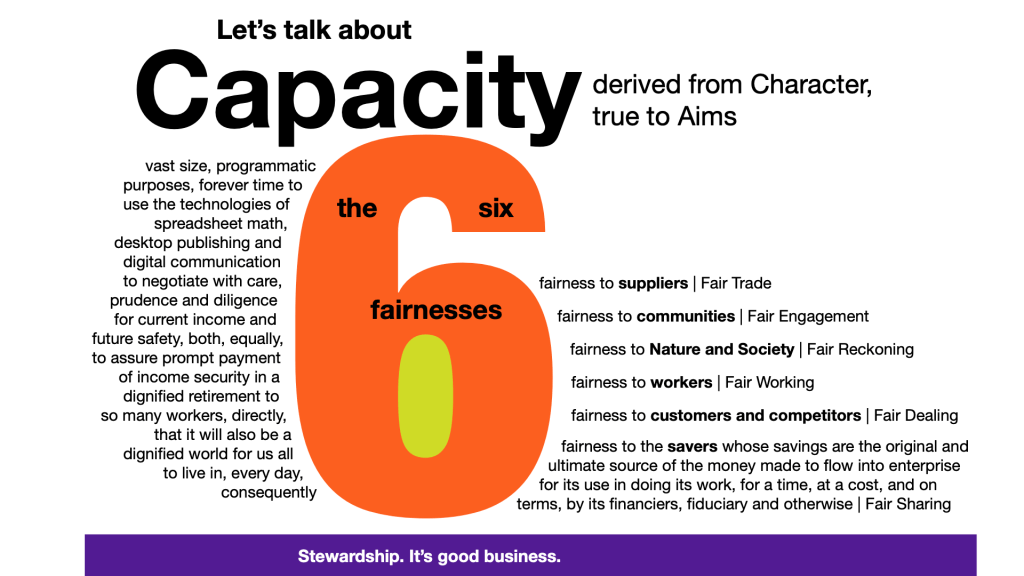

- in the exercise of capacity

- derived from character

- true to aims

Fiduciary Money

Fiduciary Money

Fiduciary Money

Fiduciary Money

Let’s talk about accountability

through popular participation in

A NEW Pension Trust Socialism

In 1976, American corporate management guru Peter Drucker published a book with title: The Unseen Revolution: How PensIon Fund Socialism Came to America.

In it, Drucker predicted that the growing amount of money controlled by pension trusts being invested in the securities trading markets would make corporations financed by the securities trading markets accountable to workers through their pensions.

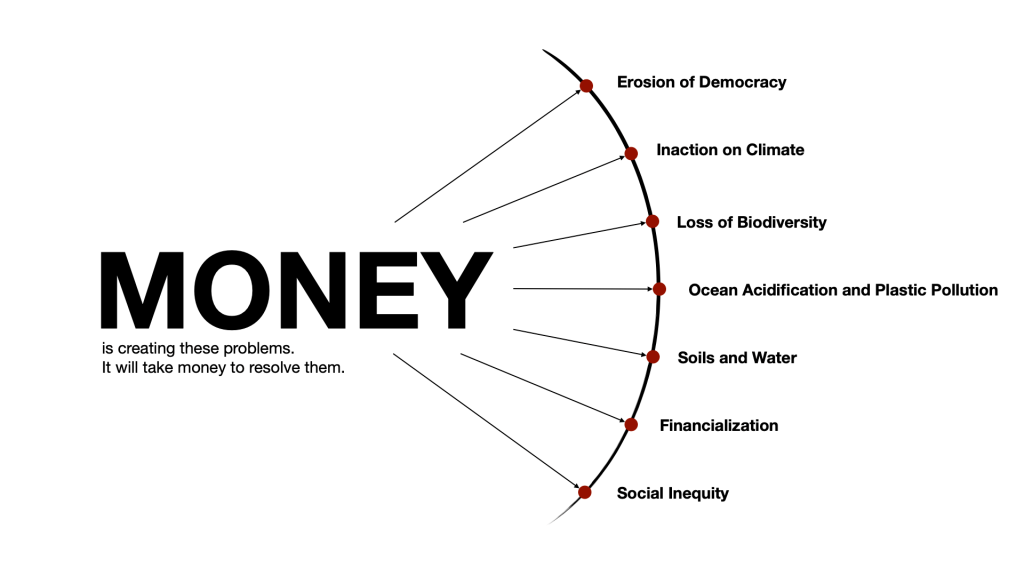

Instead, pension trusts have been made to abandon the interests of workers, and all of us, in favor of a new form of Pension Extractivism, through the financial mathematics of securities trading, as Asset Owners Allocating Assets across Asset Classes and within classes, selecting/mandating Asset Managers who are peer-benchmarked by Consultants for outperformance in maximizing the highest possible purely pecuniary profit extraction from volatility and growth in market clearing prices for securities in the markets for maintaining volatility and growth in market clearing prices for those securities, solely in the financial best interests of Asset Managers, Consultants, Corporate Executives and other securities trading markets professionals, in reliance of the fundamentally flawed and failing axiom that more money in the markets (fees and profits for them) will also always mean an improved quality of life for us.This is not working.

It’s time for an upgrade.

Technical upgrade to capabilities:

waterwheel modeling of equity paybacks

Existential upgrade to our social narrative: being human, together, and apart, in society, through economy, using money on a planetary scale in the 21st Century, and beyond…

Political upgrade: individual contributions to local community engagement in globally curated conversations for articulating an adaptive evolving common sense of fiduciary prudence and loyalty through the social innovation of Prudent Person Assemblies

a new math gets invented

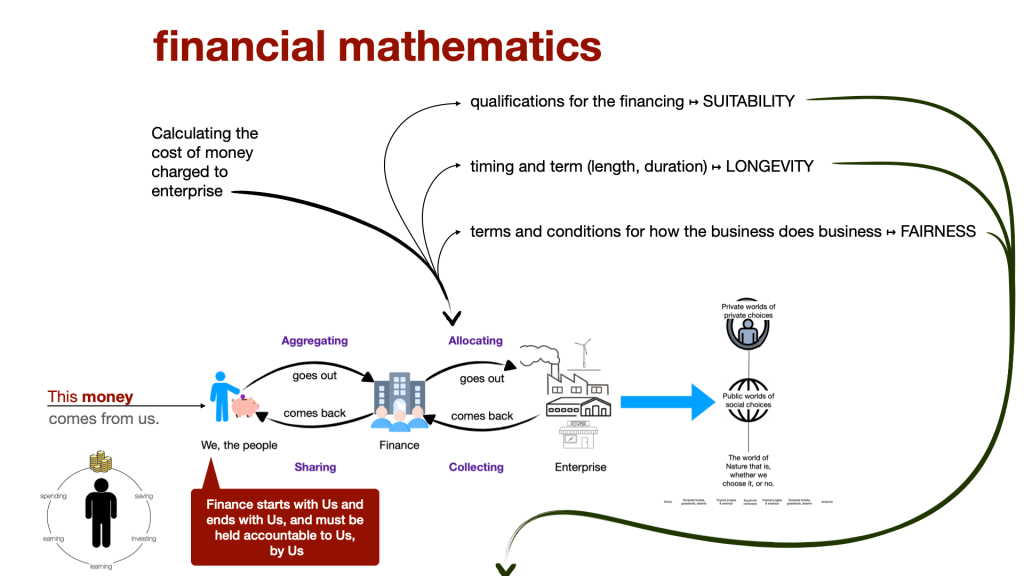

financing suitability, longevity and fairness in enterprise cash flows through equity paybacks

prudence gets updated

Private Equity 1.0 for profit extraction from ownership upgraded to Private Equity 2.0 for prudent stewardship of suitability, longevity and fairness in enterprise cash flows

a new world

becomes possible

A new 21st Century planetary citizenship in a new 21st Century planetary commons of prudence and loyalty in the allocation of fiduciary money by Pensions & Endowments using equity paybacks

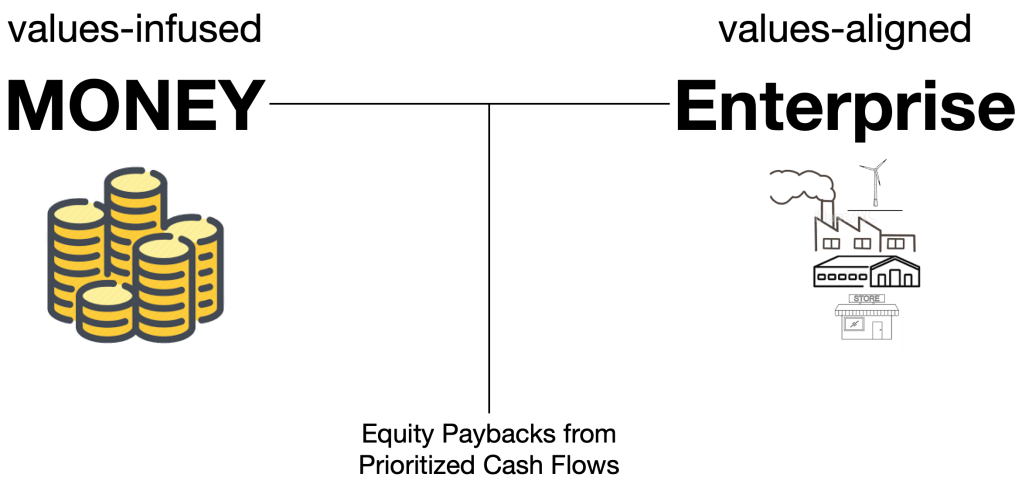

Popular participation in holding Pensions & Endowments accountable for authenticity and integrity in their exercise of the capacity they derive from their character as large, purposeful and self-perpetuating social trusts, to use the personal computing technologies of spreadsheet math, desktop publishing and digital communication to allocate the values-infused money they control to values-aligned enterprise through equity paybacks from prioritized cash flows in undivided loyalty to their aims, to invest the money society entrusts to their discretion for income as well as safety to assure income security in a dignified future to so many, directly, as a private benefit, that it is also, of necessity, for us all, as a public good

The next

great experiment for promoting human happiness

George Washington

an expedition of inquiry in the imagination, to discover and explore our uniquely human way of being in the world, in society, through economy, using fiduciary money

Money is such an important part of our lives

and yet

we rarely talk about

what it is

and how it works,

or especially

what it means.

Dave Gray,

Possibiltarian

The School of the Possible, on Zoom and on Substack

There are few words in the English language that so completely express the roiling tumult of conflict and contentiousness that is our human way of being in the world as this one word,

money.

By design, money is inert. A simple measure that in itself says nothing about the value of what is being measured. A purely factual recording of a quantity.

But what is being measured, what is being quantified by money, is our human relationships with each other; our worth, as a human, to another human. And that is very dangerous territory, this territory of our worth to others. It is a symphony of rationality and a cacophony of emotion, of thinking and feeling, of thoughtfulness and thoughtlessness, of affection and hostility, every single note of which is sounded in some way through money.

Money does not exist in Nature. It is completely made up, a purely human invention. A thing that is no thing. Nothing.

And yet it is the most powerful thing in the whole of human experience. The root of all evil. And the best revenge.

We all use money.

Some of us want it.

Some wish we did not have it.

We all need it.

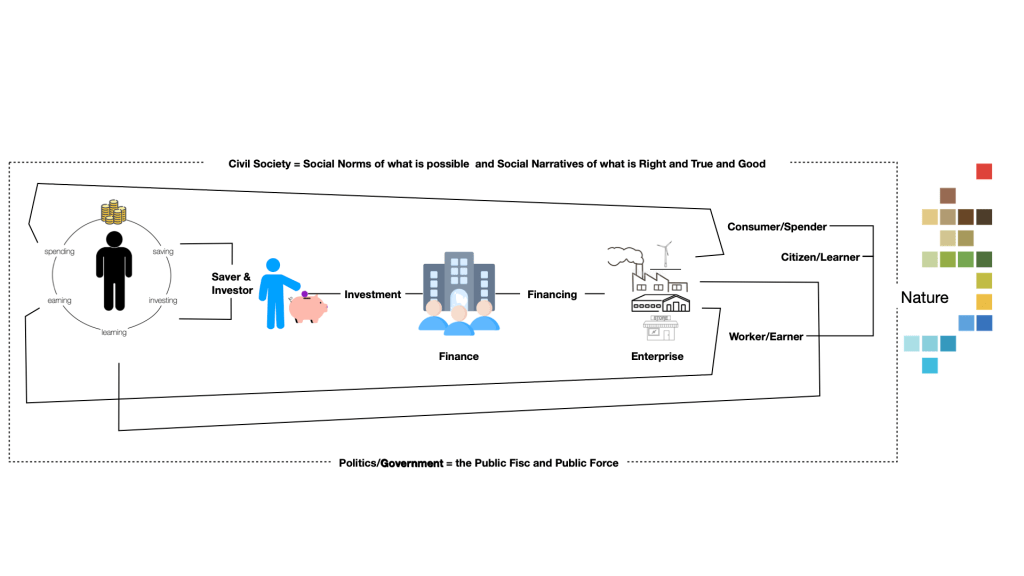

We each participate in society, through an economy of enterprise and exchange, using money:

- we learn about the choices that learning makes possible, and the rules for choosing well;

- we participate in enterprise and the work of applying learning to produce an abundance of unique artifacts of that learning, in surplus for sharing through exchange, to earn money;

- we spend some of what we earn to acquire, through exchange, for our own use and benefit, personally and privately, artifacts of that learning that we choose to use to curate our own personal and private world for living our own best life as best we can under the circumstances then prevailing, personally and privately;

- we save what we choose not to spend, and set it aside to spend on something else, at a later point in time (because we, as humans, live in time, through our learning); and

- we invest what we set aside as savings for investment in financing for enterprise, to shift some of the burden of our earning from our shoulders to our savings.

We all participate in Civil Society as citizens and learners, learning the social narratives for what is possible, and the social norms of what is right and true and good, giving us the knowledge we need to curate, personally and privately, our own personal and private worlds in which we live our own best lives, as best we can, out of the shared public world we curate together, through enterprise and exchange, out of the world of Nature into which we each are born.

We each participate in enterprise and exchange, as workers and earners (where “working” is used in its broadest meaning), and as consumers and spenders.

Through that participation, we help to shape the economy in which we all live.

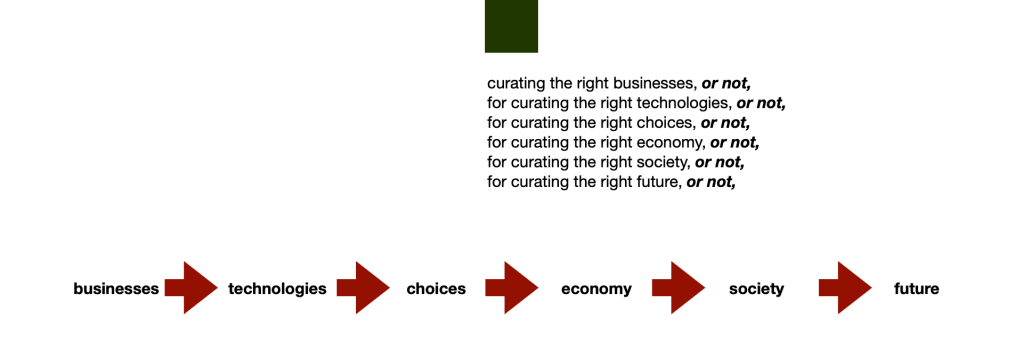

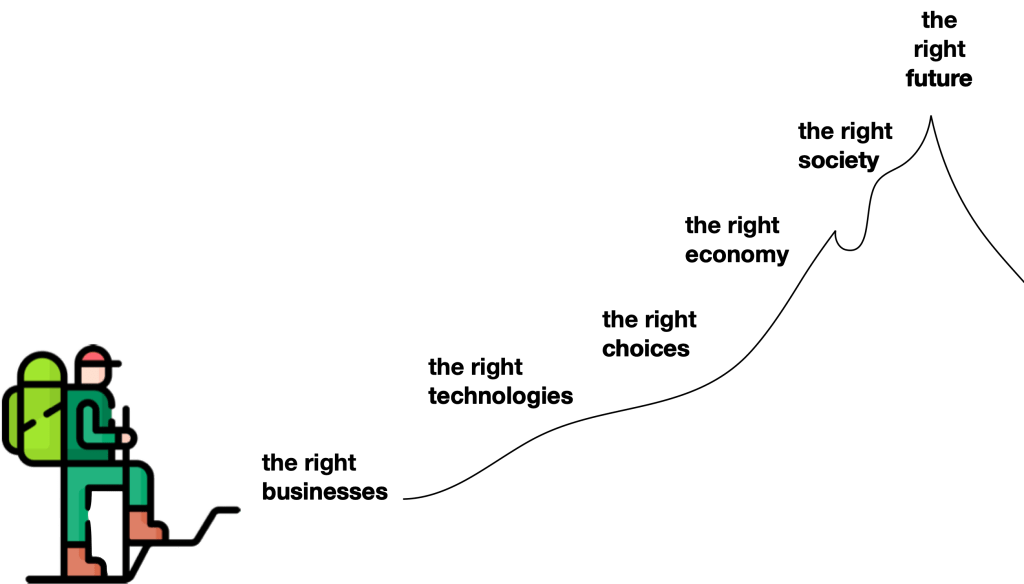

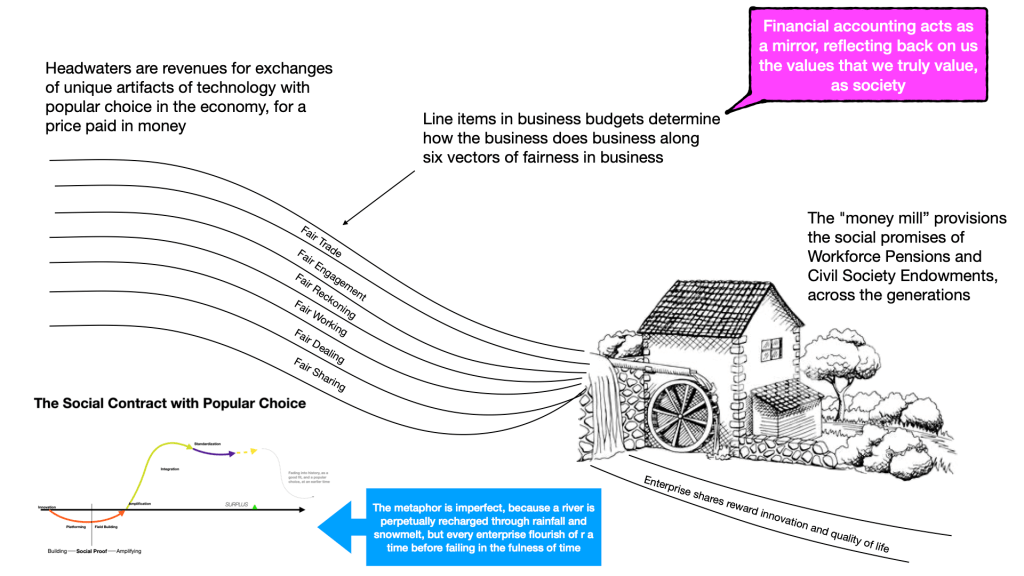

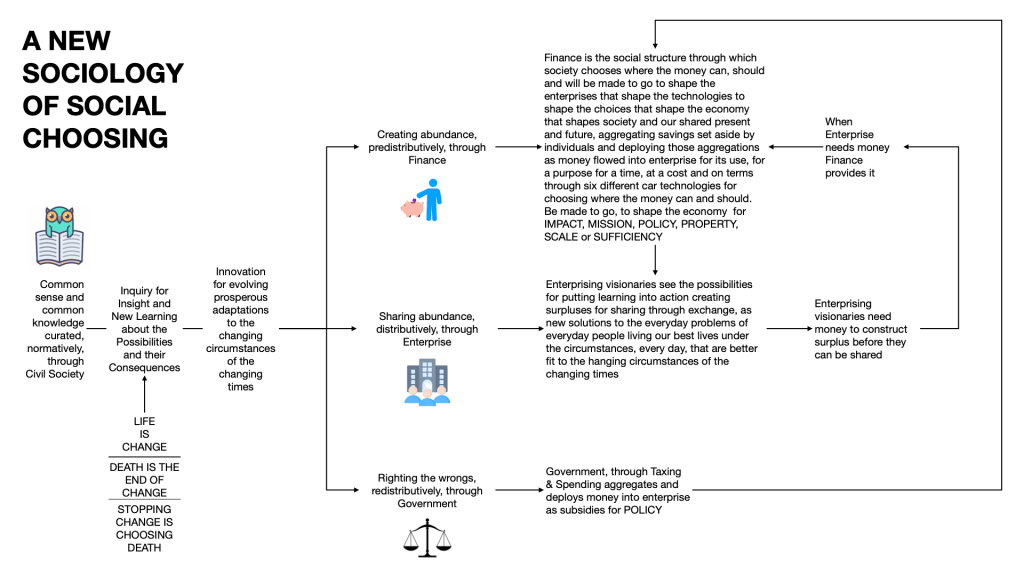

We also participate as savers who set money aside as savings for investment in financing for enterprise. Financiers aggregate our savings, and allocate those aggregations as money made to flow into enterprises, for their use in doing their work, for a time, at a cost and on terms that curate the businesses that curate the technologies that curate the choices that curate the economy that curate society that curates our future.

YOUR place in OUR economy

Few really understand it.

Because our stories about money are as confused and conflicted as the relationships that we energize through money.

To have money is to have power over others. To be without money is to be without power, forced to become indentured to others, or driven to rely on our wiles in an effort to beguile.

To be sure, there is an empirical residue of human emotion that manifests without money: the care and caring of mother for child, of family and friends; the animosities of rivals and hatred of enemies.

But mostly, people live together using money.

Given the importance of money to our human way of being together in society, it seems we should have a universally accepted and clinically precise language and vocabulary for talking about money, much the way we have a language for talking about language. We know what words are and how they are used. When they are being used correctly, and when they are being corrupted.

But we don’t know so much about money.

Why not?

towards a new language of money as a social structure for being human at a planetary scale in the 21st Century

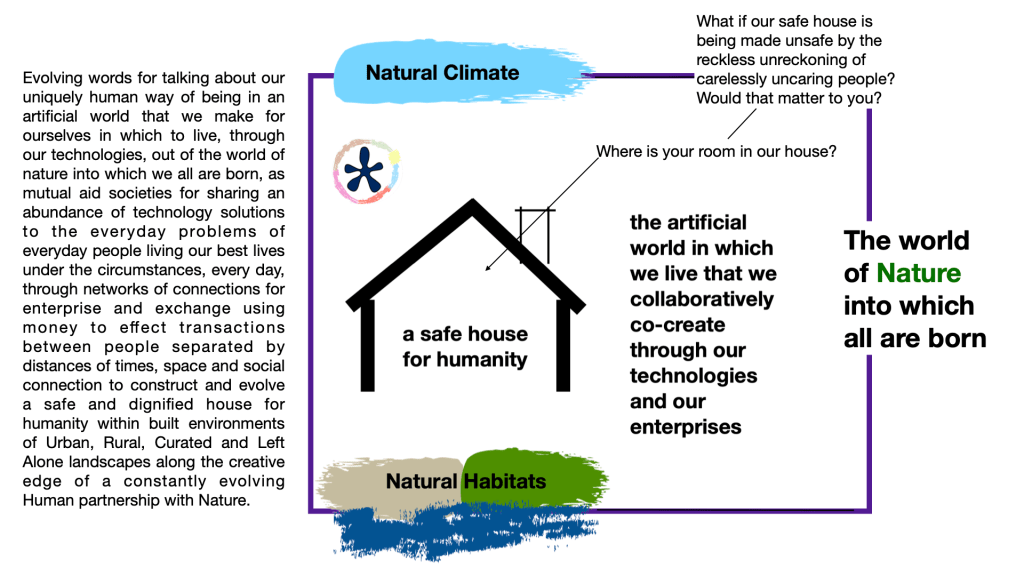

Technology is our uniquely human way of being, together, and apart, in personal and private worlds for living our own best lives, as best we can under the circumstances then prevailing, personally and privately that we each curate for ourselves, personally and privately, out of the world that we make together, socially and publlcly, out of the world of Nature into which we each and all are born, that we do mot make, nut upon which we all depend for our own personal, individual and shared, social ongoingness.

It is essentially social.

We, as humans, are essentially socialists.

It takes a concentration of time, effort and expertise to master knowledge of how the world about us works, in its various and diverse specific ways, and to apply that mastery to the work [the toil of tilling the soil] of taking the world about us as we find it, in some specific way, and changing it, in that specific way, to make it be more a way we choose to make it, in that specific way.

Such application of mastery produces an abundance of artifacts of that technology, in surplus to what we ourselves can use in making our own personal and private worlds, in which to live our own best lives, as best we can under the circumstances then prevailing.

That surplus in abundance can be shared with others, in exchange for the surpluses that they produce through their application of their mastery of other and different knowledge.

In this way, humanity creates our economy, as a mutual aid society for sharing an abundance of technology solutions to the everyday problems of everyday people, each living our own best lives as best we can under the circumstances then prevailing, everyday, through enterprise for creating an abundance of the artifacts of our technologies, in surplus, for sharing through exchange.

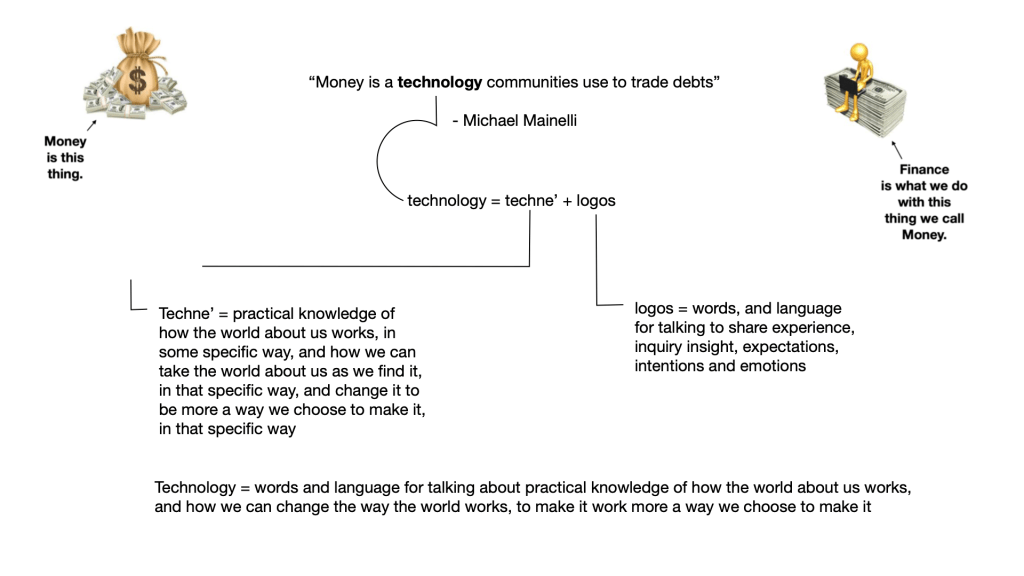

Exchange requires trust.

Money is a token that we can trust, a legal instrument that we essentially social and socialist humans use to effect exchanges between people separated by distances of time, place and social connection that create obstacles to personal trust: you do not have to trust the other person, if you can trust their money.

Money is also the social energy that society uses to direct our individual insights and initiative towards some activities (“you can make good money doing that” and away from others “there is no money to be made in that”).

a new story of

for curating your future

My Story

This is my story.

I am the producer and content creator of this website.

I choose to publish this website as a way of sharing my story, rather than writing a book, because books are linear and logical, This story, like the law of which so much of it is made, is a seamless web.

The Internet is also a web. A World Wide Web.

And this is a worldwide story, of being human on a planetary scale, in the 21st Century, together and apart, in society, through economy, using money as new 21st Century planetary citizens in a new 21st Century planetary commons of a new 21st Century social innovation of a new Pension Socialism using the new social innovation of Fiduciary Money and Fiduciary Finance using Equity Paybacks to curate, predistributively, the right 21st Century planetary economy of technological suitability, ecological longevity and basic human fairness.

Tim MacDonald

portrait by my granddaughter, aged 4

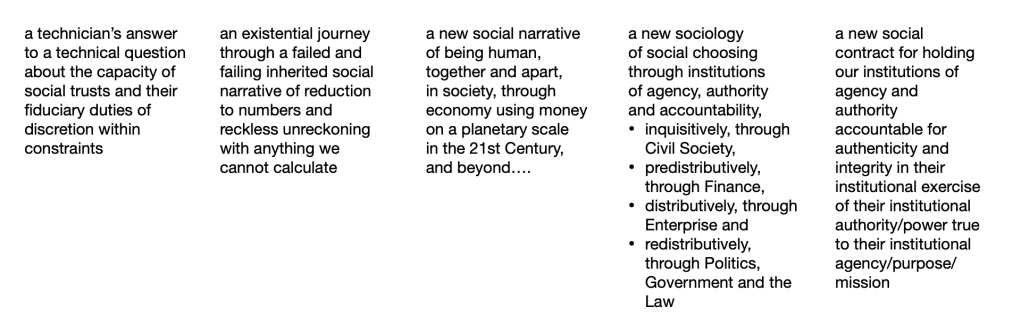

I am a technician, with a technical answer to a technical question about the capacity that a social trust for workforce pensions and civil society endowments derives from its character.

That technical question about capacity launched me on a philosophical inquiry onto Money and Finance and Enterprise and Technology and Politics and the Economy and our uniquely human way of being in a world we make for ourselves, in which to live, out of the world of Nature into which we each and all are born through enterprise for the exchange of an abundance of technology solutions to the everyday problems of everyday people living our own best lives, as best we can under the circumstances then prevailing, everyday.

This website shares the learning that I learned on my journey through that inquiry.

It is a story told in words and images, about the meaning of those uniquely human innovations: words and images.

1.

A Technical Answer to

a Technical Question

I am descended from Scottish immigrants to North America. Specifically, to southern New England by way of Nova Scotia. The son of a city worker, a firefighter for the City of Fall River, Massachusetts.

The Spindle City.

In its heyday, Fall River, Massachusetts USA was a major industrial center for textile manufacturing. Clothing. The thing we humans need most, after food, for comfort and protection against the elements. Also, Fashion. The thing we humans need most for delaying our identities, expressing our personalities, and declaring our position in the social order of things.

That was before my time.

If you know the story of Warren Buffet, you will know that his company, Berkshire Hathaway, Inc., started out as a conglomeration of the Berkshire Mills, in Fall River, and the Hathaway Mills, in nearby New Bedford. Plus other textile holdings elsewhere.

If you are a literary person, you will know New Bedford as the port of call for Ishmael, the recanteur in the great American novel by Herman Melville, Moby Dick.

In its heyday, New Bedford was the energy capital of the world, in a world that lit the darkness by burning whale oil. It had more wealth per capita than any other place on earth.

Not so today.

And not so in 1965, when a young aspiring financier named Warren Buffet, first striking off on his own after apprenticing with Benjamin Graham, who taught him the “cigar butt” approach to investing:

“buy something so cheap that, even if the business is mediocre, you can get “one last puff” of profit.”

Tom Spain, https://www.linkedin.com/posts/tom-spain-828b2417_warrenbuffett-berkshirehathaway-investing-activity-7360005391696445440-_pnR?

thought he had found in the Berkshire Hathaway Corporation a business he could buy cheap enough to get one last good puff of profit from it.

Buffet would later describe the purchase as

“a soggy cigar butt: not just one puff left, but a poor smoke even if you got it for free” (Tom Spain)

A Lesson from GEICO

Buffett had long understood the potential of insurance. As a young Columbia student in the 1940s, he had studied GEICO, a company Ben Graham once owned. In 1951, he even travelled to Washington, D.C. to talk with GEICO executives.

The key lesson stuck: insurance companies collect premiums now, but only pay claims later. The cash they hold in the meantime is called float.

For a capital allocator like Buffett, this was an irresistible model — leverage without debt, and permanent capital to reinvest.

I learned about this thing that Tom calls float as a young lawyer in the tax syndication business, based in Boston, in the 1980s.

Not in Property & Casualty Insurance, but in Life Insurance, where it is not called float (“float” is the time banks have use of our checking account deposits between the time a check is written and the time the settlement date, when the check is honored by the bank – a pre-digital era concept) but policyholders’ premiums.

All insurance companies today (at least those doing business in the United States) are regulated as to their investment activities by something called the Legal List. This is a list of investments approved by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners, as lawful investments by regulated insurance companies.

This Legal List dates back to the Gilded Age of securities fraudsters, Robber Barons and Trusts for monopolizing industries to fix prices, such as in Sugar and Steel. Much of this financial malfeasance was in fact financed by an unholy alliance between Wall Street and the new-tech of its time, life insurance business. Insurance companies who controlled vast sums of money aggregated from policyholders, to fund policy payouts, teamed up with securities trading markets professionals to finance financial engineering as an earlier, 19th Century form of late 20th Century hostile takeovers, fueling securities trading markets pricing booms that went bust in the Panics of 1893 and 1907, almost bankrupting the US Treasury, and requiring Teddy Roosevelt to ride in and bust up the trusts, while state legislatures passed laws regulating insurance, and creating the Legal List.

We had a repeat of this unholy alliance between vast aggregations of other people’s money and financial engineering on Wall Street in the Roaring Twenties, when Wall Street teamed up with Depositary Banking to fuel another securities taxing markets boom. This one went bust in the Crash of ’29 and the Great Depression (teaching us this inconvenient truth about the securities trading markets: every boom is just a bust that has not happened yet).

We are living through a third Unholy Alliance today. This time, with Pensions, in the form of Asset Owners Allocating Assets Across Asset Classes, and within classes, selecting/mandating Asset Managers who are peer-benchmarked by Consultants for outperformance in maximizing the highest possible purely pecuniary profit extraction from volatility and growth in market clearing prices for securities in the markets for maintaining volatility and growth in market clearing prices for those securities, solely in the financial best interests of Asset Managers, Consultants, Corporate Executives and other securities trading markets professionals, in reliance upon the axiomatic assertion that more money in the markets (fees and profits for securities trading markets professionals) will alway also mean improvement in the quality of life for all of us.

This promise that more for them is better for us is the foundational principle of the philosophy of humanity known as Neoliberalism that shows us the economy as the production and distribution of goods and services through markets for allocating scarcity using price.

This Neoliberal economy calls on each of us, and all of us, to work hard to produce and consume more, so that the markets can give us more (as an antidote to scarcity), on the promise that more will always be better, and that each of us, as freely self-determining market participants will always be free to freely determine, each for ourselves, our own fair share of that more that is better.

This Neoliberal philosophy that more quantities of money in the markets means a better quality of life for all is the fundamental rationale underlying the prevailing popular social contract for agreeing that growth as the simple, numerical increase in qualitatively undifferentiated transaction volumes, measured in prices paid in money, is both necessary and sufficient to the longevity of our shared prosperity.

Which brings us back to Warren Buffett, and his use of insurance company “float” (= policyholders’ premiums) to finance his acquisition of “cigar butt” enterprises.

None of these acquisitions would qualify under the Legal List. But somehow, Buffett managed to get dispensation to invest outside that List.

That is the true secret to Buffett’s success.

It is the clue to the success that Pensions & Endowments, and all of humanity, can and should be having, with one modification: where Buffet bought to own, Pensions & Endowments can and should buy to steward, through equity paybacks from prioritized cash flows.

Today, they are not either buying to own or using the financial math of equity paybacks to prioritize cash flows. And this is a problem.

Instead, prevailing popular practice has Pensions & Endowments shackled to the locked imaginary of Growth as both necessary and sufficient to the longevity of our shared prosperity, financing the securities trading markets through the financial mathematics of ownership for profit extraction as gain on sale, that bends the loyalties of these social trusts away from the security and dignity of some, and all, and towards the selling prices of the securities they buy.

This wasn’t always the case.

Before 1972, fiduciary practice was governed by something called the Legal List. This is a court-made rule of convenience, evolved in the context of estate planning trusts for mediating the tensions between an income interest and a remainder man, that limited fiduciary discretion when making investments to a short list of “safe” (= prudent in the language of the law) investments: mostly interest paying government bonds and loans secured by mortgages on real estate.

I see in this rule of the Legal List a defaulting to a royal sense of safety, when economies were agricultural, land was wealth and government was the king, who owned the land.

Do you?

Then, in 1969, advocates for the self-interest of securities trading markets professionals prevailed upon Ford Foundation to commission a study of the law of fiduciary duty, specifically as it applies to trusts for university endowments, in light of recent new learning about price risk management in the securities trading markets that we now know, colloquially, as Modern Portfolio Theory.

PORTFOLIO SELECTION*

*This paper is based on work done by the author while at the Cowles Commission for Research in Economics and with the financial assistance of the Social Science Research

HARRY MARKOWITZ

The Rand Corporation

The Journal of Finance

Vol. 7, No. 1 (Mar., 1952), pp. 77-91 (15 pages)

Council. It will be reprinted as Cowles Commission Paper, New Series, No. 60.

A review of the law was duly performed by two New York lawyers, William L. Cary and Craig T. Bright, who concluded correctly that donative trusts for endowments have broad discretion over investment decisions, constrained only by the requirement of prudence and loyalty.

The Legal List is not the law, so much as a “rule of thumb” followed by the courts when applying the law, which specifies only discretion within the constraints of prudence and loyalty, according to the factual/evidentiary standard of prudent people who are family with such matters, under the circumstances then prevailing.

Messers. Cary and Bright went on to argue that since “men of business” commonly buy and sell securities for their own account through properly diversified portfolios, endowment trusts could – not in the sense of “can” but more in the sense of “might” – also buy and sell securities through diversified portfolios.

The report concludes that there are no legal impediments hampering managers of educational endowment funds in their efforts to develop sound investment policies

https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED041559

This was 1969.

In 1970, Milton Friedman self-declared his infamous Friedman Doctrine in an article published in The New York Times,

A Friedman doctrine – the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits

Milton Friedman

Sept. 13, 1970

https://www.nytimes.com/1970/09/13/archives/a-friedman-doctrine-the-social-responsibility-of-business-is-to.html

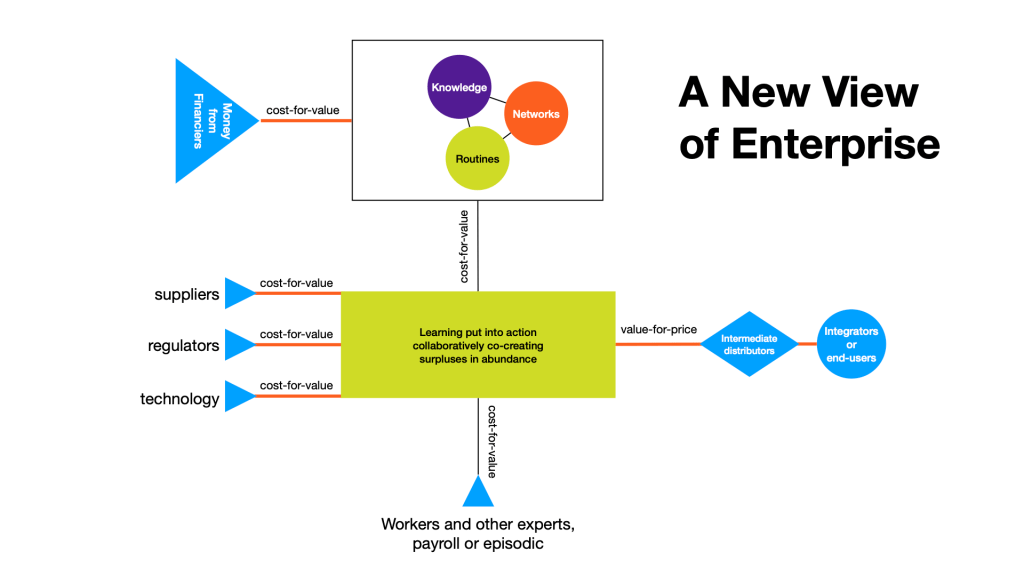

In articulating this “doctrine”, Friedman surreptitiously equates business, as the social organization of physical Knowledge, Networks and Routines aligned to offer an abundance of unique artifacts of technology to popular choice, in exchange for a price paid in money, or other value that can be converted into money, with the corporation, which is a legal form of ownership for investment and control over enterprise as a social reality.

The corporation is a preferred legal form for securitizing the ownership of enterprise into large numbers of legally equal, commodity shares that can be bought and sold as securities to extract profits from volatility and growth in market clearing prices for those securities, in the markets for maintaining market clearing prices for those securities.

The corporation is a financing agreement favored in a particular form of financing through securitization for profit extraction from volatility and growth in selling prices for securities.

The enterprise that chooses to finance its work by incorporating to securitize its shares does enter into a social contract with the markets that own its shares, to support volatility and growth in the market clearing prices for those securities, because those markets require volatility and growth in market clearing prices to function according as they are designed.

This it does by increasing its profits.

If a business does not finance its activities through securitization, then it has no obligation to increase its profits. The business is free to do business however it chooses, provided it does so lawfully.

This is the true freedom of “free enterprise”. Not the freedom to grow by whatever means necessary, whatever the consequences for others, now or in the future, because that is what the securities trading markets require of the enterprises they finance.

We will see this kind of linguistic sleight of hand, that substitutes the needs of securities trading for the good of society, while talking like the concern is actually with the social good, repeated over and over again on the journey of fiduciary practice from lawful Prudent Stewardship to unlawful Asset Ownership.

We see it next in 1971, when Lewis Powell submitted a Confidential Memorandum: Attack of American Free Enterprise System to the United States Chamber of Commerce that opens with the declaration:

No thoughtful person can question that the American economic system is under broad attack*.

The asterisk states

Variously called: the “free enterprise system,” “capitalism,” and the “profit system.” The American political system of democracy under the rule of law is also under attack, often by the same individuals and organizations who seek to undermine the enterprise system.

Powell asserts:

The most disquieting voices joining the chorus of criticism come from perfectly respectable elements of society: from the college campus, the pulpit, the media, the intellectual and literary journals, the arts and sciences, and from politicians.

Basically, all of Civil Society is identified with an imagined attack on a vaguely identified “American economic system”, calling for a broad -based counteroffensive to seize control of the social narrative that includes:

- Staff of Scholars

- Staff of Speakers

- Speaker’s Bureau

- Evaluation of Textbooks

- Equal Time on the Campus

- Balancing of Faculties

- Graduate Schools of Business

- Secondary Education

- What Can Be Done About the Public?

- Television

- Other Media

- The Scholarly Journals

- Books, Paperbacks and Pamphlets

- Paid Advertisements

- The Neglected Political Arena

- Neglected Opportunity in the Courts

- Neglected Stockholder Power

- A More Aggressive Attitude

Then this call to action:

It is time for American business — which has demonstrated the greatest capacity in all history to produce and to influence consumer decisions — to apply their great talents vigorously to the preservation of the system itself.

What, exactly. is this “system” that Powell claims is under attack?

Lewis never actually defines that system. For an answer, we have to look to who he names as the enemies of this “system”.

Chief among these is consumer rights activist, Ralph Nader, who Lewis describes by sharing this quote form an article published in Fortune magazine:

“The passion that rules in [Nader] — and he is a passionate man — is aimed at smashing utterly the target of his hatred, which is corporate power. He thinks, and says quite bluntly, that a great many corporate executives belong in prison — for defrauding the consumer with shoddy merchandise, poisoning the food supply with chemical additives, and willfully manufacturing unsafe products that will maim or kill the buyer. He emphasizes that he is not talking just about ‘fly-by-night hucksters’ but the top management of blue chip business.”

Notice the linquistic legerdemain at work here, as Lewis subtly equates “corporate” and “business”, implying, but never openly stating, that objections to corporate abuse of power are somehow an attack on freedom in enterprise.

But businesses are a social reality, the physical coming together of people to organize knowledge, networks and routines for constructing an abundance of artifacts of technology for sharing with others in exchange for a price paid in money, or other value that can be converted into money.

The corporation is a legal form of ownership for investment and control over enterprise through the securitization of ownership for profit extraction as gain on sale into large numbers of legally equal, commodity shares that can be bought and sold, idiosyncratically and opportunistically, to extract profit form volatility and growth in the market clearing prices for shares as securities in the markets for maintaining volatility and growth in market clearing prices for those securities.

If we expand “corporate” and “business” into “corporate financing for business enterprise”, we see that the system they are defending is not a system of freedom in enterprise. It is a system of financing for enterprise: the system for financing enterprise through securities trading.

Ralph Nader was one of the most popular voices in the late 1960s ongoing into the 1970s raising the hue and cry against this false assertion that “more for them” is “better for us”, citing allegations of “defrauding the consumer with shoddy merchandise, poisoning the food supply with chemical additives, and willfully manufacturing unsafe products that will maim or kill the buyer”.

His Call to Action was for the federal government, through force of regulation, to lay down guardrails for how business can do business, in the interest of the wellbeing of the population, generally.

This is not an attack on the freedom of business to do the business it chooses to do, except to the extent that every law is a constraint on the freedom of people to do harm to other people, whether through negligence, malice or greed.

It is a constraint on the ability of corporations to externalize costs in order to increase profits, to meet the demands of the securities trading markets, for growth in market clearing prices.

This is the system that Lewis Powell is actually defending: a system of extractive externalization in corproate finance.

It is a system of Enterprise Finance, that Powell, and also Friedman, is defending.

Not a system of Enterprise, itself.

There is an important difference between the two.

We will see this trick of trying to misrepresent critiques of securities trading as a way of financing enterprise as critiques of freedom in enterprise. Which they almost never actually are.

The year after he produced this memo, Lewis Powell was elevated to Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court by Richard Nixon.

That was 1972.

Also in 1972, the National Commission on Uniform State Laws promulgated something they called the Uniform Management of Institutional Funds Act, which effectively wrote into law the conclusion of the Cary & Bright Report to Ford Foundation, “that there are no legal impediments hampering managers of [institutional] endowment funds in their efforts to” invest in securities trading in reliance on portfolio diversification according to Modern Portfolio Theory.

Nominally, the Uniform Act, which has since become law in almost every state in the United States, replaced the Legal List with the Prudent Person Rule, which in and of itself is unremarkable.

In practice, it replaced the Prudent Person with the Prudent Investor. Also, in and of itself, a seemingly unremarkable distinction without a difference, since the person at issue is also an investor of money entrusted to their discretion. But the generic term, “Investor”, was actually being specially encoded with the specialized meaning of “participant in the securities trading markets”.

A new lore was being constructed that required social trusts for Endowments to become, first, Institutional Investors in the securities trading markets, and later, Asset Owners whose duty is to Allocate Assets Across Asset Classes, and within classes, to select/mandate Asset Managers who are peer-benchmarked by Consultants for outperformance in maximizing the highest possible purely pecuniary profit extraction from volatility and growth in market clearing prices for securities, in the markets for maintaining market clearing prices for those securities, solely in the financial best interests of Asset Managers, Consultants, Corporate Executives and other securities trading markets professionals, in reliance on the axiomatic assertion that more money in the markets (fees and profits for them) would also always mean improving quality of life for us.

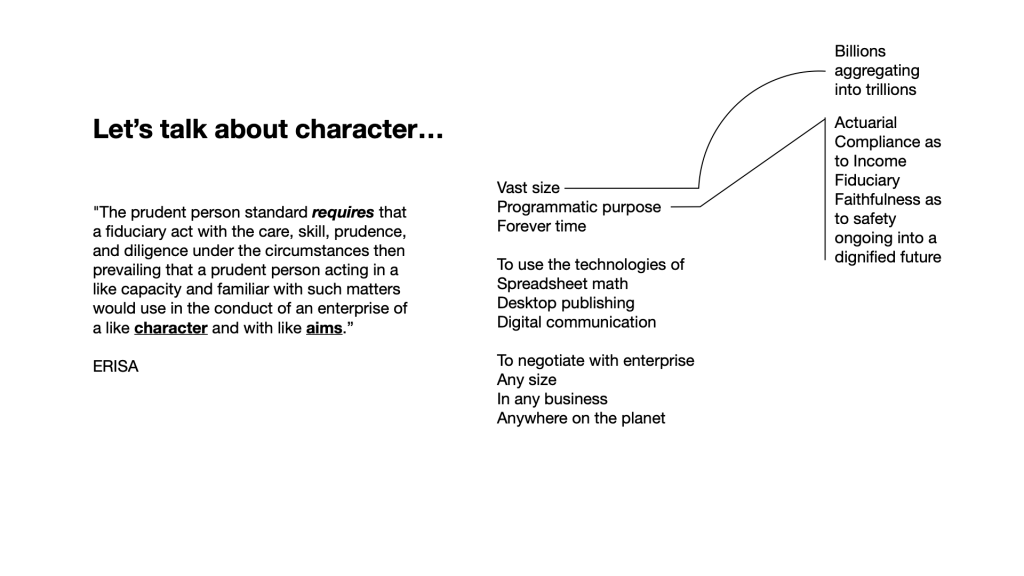

The law pushed back against this false theory of more for them is better for us in 1974, when the United States Congress passed into law the Employee Retirement Income Security Act, to curb rampant abuses in corporate pensions, by declaring:

The prudent person standard requires that a fiduciary act with the care, skill, prudence, and diligence under the circumstances then prevailing that a prudent person acting in a like capacity and familiar with such matters would use in the conduct of an enterprise of a like character and with like aims.” – ERISA

This should have shifted the focus of fiduciary practice in the context of a pension trust (and also endowment trusts) back to the question of the capacity that such a trust derives from its character as large, purposeful and self-perpetuating forever machine and its aims, to invest money for income as well as safety to assure income security in a dignified future for so many, directly, as a private benefit, that it is also, of necessity, for us all, consequently, as a public good.

But that shift did not happen. At least, it hasn’t happened yet.

In 1976, Peter Drucker published his book The Unseen Revolution: How Pension Fund Socialism Came to America, in which he prognosticated the takeover of corporate ethics by Union Labor.

The takeover did not happen. At least it hasn’t happened yet.

The truly unseen revolution, that also hasn’t happened yet, actually became possible only in 1983, when Mitch Kapor released his Lotus 1•2•3 suite of software for the IBM PC running MS DOS.

That innovation made the power of spreadsheet math, desktop publishing and digital communication widely available within business.

Which brings us back to Warren Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway and the purchase of businesses for their ability to make money, to share in profits as earned, not to extract profit from growth as gain on sale, and the use of insurance company policyholders’ premiums to finance those acquisitions.

Combine that with the standard mathematics of Real Estate financing through negotiated agreement on equity paybacks to an agreed cost of money, reducing to evergreen ratable sharing, from enterprise cash flows prioritized by contract for valuing the values that the suppliers of money value, and apply that to the capacity that Pensions & Endowments derive from their character, as large, purposeful and self-perpetuating social trusts, to use the personal computing technologies of spreadsheet math, desktop publishing and digital communication and you get the innovative new fiduciary financial mathematics of waterwheel modeling of equity paybacks to an actuarial/fiduciary cost of money, plus opportunistic upside, from enterprise cash flows prioritized by contract for valuing the prudent stewardship values of:

- suitability of the technology to the circumstances then prevailing at the time;

- longevity of the social contract between the enterprise and popular choice over time; and

- fairness in how the business does business across all six vectors of fairness in business, all the time.